Throughout history, governments and armies have conspired to brutally wipe out entire groups of people through mass murder and the destruction of social and cultural structures, in an ancient practice that since World War II has been labeled by the term genocide.

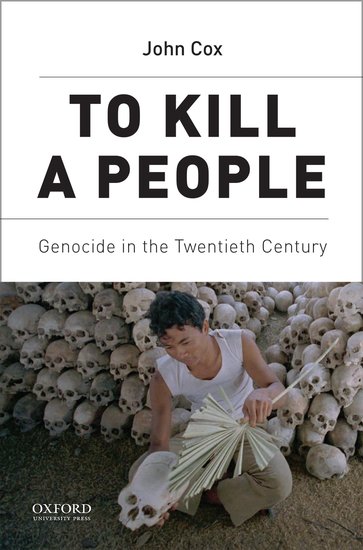

John Cox, director of UNC Charlotte’s Center for Holocaust, Genocide & Human Rights Studies, has offered a new perspective on the meaning and significance of genocide in his book, To Kill a People: Genocide in the Twentieth Century (Oxford University Press). Cox is an associate professor in the Department of Global, International & Area Studies in the College of Liberal Arts & Sciences.

Reviewers have praised Cox’s book for combining an expert grasp of the causes and dynamics of genocide with an impressive command of the scholarly literature. It is also “distinguished by a humane critical perspective, founded on the belief that genocide is not inevitable or necessarily an eternal feature of human affairs,” one reviewer stated.

Adam Jones, an internationally renowned genocide scholar and author or editor of more than 20 books, called the work “galvanizing” and said it will “long be read, studied, and appreciated by students and other concerned citizens.”

Many Holocaust and genocide scholars are drawn to the subject because of their family backgrounds. This was especially true in earlier years of Holocaust research.

“I came to these issues in a more indirect, but also personal way,” Cox says. “I grew up in Greensboro, North Carolina being very aware of racism and other injustices in our society, and in college I became involved in the anti-apartheid movement. I was also prompted to activism as well as research by learning about the role of U.S. policy and interests in Latin America. My research found that in the 1980s and at other times the U.S. has supported genocidal regimes in Guatemala and elsewhere.”

Cox’s first book, Circles of Resistance: Jewish, Leftist, and Youth Dissidence in Nazi Germany, was published in 2009 and analyzes resistance organizations of young German Jews and other dissidents under the Nazi dictatorship.

“In my first book, and in other writings, I have focused on anti-Nazi resistance,” Cox says. “In To Kill a People, I attempted to analyze resistance in other times and places, and I am currently working on a comparative examination of resistance, defiance, and nonconformity under various authoritarian or genocidal regimes.”

To Kill a People explores resistance and rescue in addition to its analysis of the social, historical, and cultural forces that produce genocide violence.

“The study of history can be overwhelmingly depressing, and obviously nothing is more dreary than the study of genocide,” he says. “Yet it is important to learn that, even under the most crushingly oppressive regimes, the human impulse for solidarity and freedom has never been extinguished. In each chapter, I attempt to show the full range of responses, including resistance, rescue, and nonconformity, in accurate proportion.”

Book Draws From Four Case Studies

Cox’s new book details four case studies—the Armenian Genocide, the Holocaust, and the genocides in Cambodia and Rwanda. Although To Kill a People focuses principally upon the 20th century, Cox anchors many of his core arguments in examples of centuries-old atrocities.

“Genocide is a uniquely sinister, irreparable crime by seeking not only the physical elimination of large numbers of human beings, but, more permanently, the eradication of the means of sustaining a culture or ethnicity,” Cox says. “At the same time, logic and compassion dictate that any examination of genocide includes instances of mass killing that fall short of our working definition of genocide. Genocide shares many characteristics and dynamics with non-genocidal mass murder, another reason we should not rigidly describe the two.”

John Cox teaching

Few reasonably concise overviews of genocide exist, Cox says, which makes his book an important contribution.

“Beyond that, I think my book is distinguished by its emphasis on racism—intertwined with nationalism and war—as the key factor in modern genocide,” Cox says. “I am certainly not alone in stressing racism and ethnic nationalism, but other comparable books have stressed other factors.”

Cox offers his own definition of genocide, which provides sharp critiques of certain features of the most widely recognized definition. “I also developed my own ‘timeline of genocidal violence,’ which contains episodes of colonial violence – Congo under King Leopold II, France in Algeria, the U.S. in Vietnam – that are rarely termed ‘genocidal,’ but should be. The book also includes a chapter-length bibliographic essay, which no other such book possesses.”

Cox says he wants to reach a large audience, while simultaneously making a strong contribution to his field of study.

“To Kill a People has received praise from some top genocide experts,” he says. “I’ve learned that the book was adopted for two Holocaust teacher-training conferences during the summer. In both cases, the organizers were looking for a book that placed the Holocaust in a larger context.”

Cox seeks to encourage people to think of themselves as global citizens and to recognize the unity of the human race. “I also hope that readers of this book will come to understand that these are universal human problems – that is, the impulse or tendency to commit horrible crimes against one another. None of us are immune. Under certain circumstances, and especially under the pressures and moral compromises of wartime, any of us are capable of conducting ourselves like the My Lai murderers, the Interahamwe death squads in Rwanda, or Nazi forces in Poland and elsewhere.”

The book attempts to challenge its readers in many ways, Cox says. “I think it is essential that U.S. citizens, who will be the large majority of my book’s readers, learn and reflect upon crimes against humanity that have been and are committed in their name, directly or indirectly. It is very easy to condemn human-rights abuses halfway around the globe, but one thing we should have learned from past genocides is that citizens need to challenge their own governments. After 40 years, Vietnam is still a nearly forbidden topic of honest inquiry in this country.”

Cox emphasized that individuals make choices, although these may be under circumstances difficult to imagine.

“We also have it within ourselves to ‘do the right thing,’ so to speak,” he says. “Genocidal violence can begin with small acts that go unopposed; similarly, resistance can begin with small acts or gestures, which then have a rippling effect. One thing we should learn from history is the necessity to be vigilant in defending human rights, and to stand up against bigotry and injustice, and to not keep silent, waiting for the storm to pass. It might not.”

Words: Kendra Sharpe