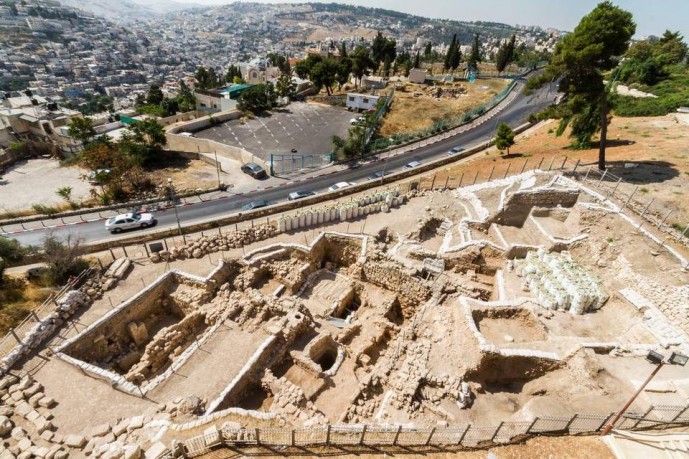

Jerusalem, rich in culture, history and historical conflict, is the spiritual capital of the Western world. Since 2007, a large, complex archaeological excavation has been conducted there under the direction of UNC Charlotte, the only non-Israeli university currently authorized to dig in the holy city. It is an archaeological investigation perhaps unlike any other.

The site is located at the city’s Mount Zion, near the Zion Gate and under the Old City Wall. It is a project envisioned and directed by Shimon Gibson, a widely respected archaeologist on the Middle East and adjunct professor at UNC Charlotte, and Professor of Religious Studies James Tabor, an authority on the area’s religious history.

Each summer, about 80 volunteer participants work two-week shifts for a month. Most years, 15 to 20 UNC Charlotte students participate through an education-abroad program. It also draws participants from around the world, with a mixture of ages and backgrounds, from students to retirees, which gives students a chance to interact with people with diverse experiences.

Five days a week, the crew rises well before dawn, meeting at 5 a.m. to trudge through the narrow streets of the ancient city to the site. They pass through Zion Gate, its stones still pockmarked by bullet holes from when the Arabs and Israelis battled for control of the city in the 1967 Six-Day War.

A rare architectural feature in one Roman-period structure is a bathroom with a bathtub attached to a mikveh, a Jewish ceremonial bathing pool. Image: Shimon Gibson.

This is a place that resonates with all kinds of history. Within a stone’s throw of the dig sits the traditional tomb of David, hero of the Bible and the city’s great king, and the room where Jesus and his disciples celebrated the Last Supper before the passion and crucifixion. Also close are the ruins of Byzantine emperor Justinian’s great Nea Ekklesia church as well as a modern apartment rented by David Koresh before he went to Texas to tragically lead the Branch Davidian sect.

“In Jerusalem, you can still touch stones that Jesus certainly walked upon and some of the structures and wall he knew,” Tabor says. “Of course, most of these are now buried several meters beneath the streets.” He speaks of a section of the Roman-era city wall that has been excavated below the roadway.

With so much big history all around, an opportunity to dig down into the ground and touch it — to uncover original stones and artifacts once built and touched by people involved in major historical events — proves irresistible to the many volunteers who put up with the dust, the heat and the hard, hard work.

The diggers come down the hillside from Zion Gate every morning as the sun first starts peeking golden over the spires on the Mount of Olives and the excavation gates are unlocked. Among them are UNC Charlotte students and alumni, professional archaeologists and retirees, donors and successful business people, dig novices and archaeology veterans. The dig is an adventure they are sharing.

Tantalizing Historical Area

At the project’s start, no one really knew what the excavation would find. When Gibson and Tabor received a license to excavate from the Israeli Antiquities Authority in 2000, they began to perceive the potential. Yet, full-scale operations did not begin until 2007 because of political tensions and unrest in the city.

Information about the area proved sketchy but tantalizing. The site was a vacant strip of land that a renowned Israeli historian and archaeologist named Magen Broshi had probed in the 1970s as part of a large series of digs to survey what might lie buried just beyond the city’s 16th-century Turkish walls. Broshi’s findings were unpublicized, but Gibson had observed the excavations as a child and remembered that some ruins of buildings had been partially uncovered.

Though the site’s contents were unknown, Gibson and Tabor suspected the site might contain something important.

Though the site’s contents were unknown, Gibson and Tabor suspected the site might contain something important.

“It may look like a vacant out-of-the-way spot in our time, but Jerusalem and its walls have shifted around over the millennia,” Tabor says. “Back in the time of Herod, this was at the center of things.”

Through the ages, many important buildings had been close by. The palace of the Jewish high priest Caiaphas (or of Annas, his father-in-law) was reported to be there in the time of Jesus. Byzantine emperor Justinian’s huge cathedral, Nea Ekklesia, was on the hillside above in the sixth century, and a massive Ayyubid Tower, built by Saladin’s nephew, was there in the 13th century.

Further, the site was on a fairly steep slope immediately below the once destroyed and later rebuilt city wall, which meant that a lot of detritus was likely to have fallen or been pushed from above, burying abandoned buildings during periods of destruction or construction.

Unlike most places in the old city, original structures here might have been buried and preserved while historical change occurred above them.

When UNC Charlotte began full-scale digs in 2007, excavators found a complex of ruins more extensive than anyone had dared believe would be there, representing a variety of historical periods — first-century Herodian Roman, sixth-century Byzantine and later Islamic times. The investigators also found an archaeological situation of astounding complexity.

Gibson notes that the oldest houses in the area were first-century homes abruptly abandoned when the Romans destroyed Jerusalem in A.D. 70 because of a Jewish revolt.

“The ruined field of first-century houses in our area remained there intact up until the beginning of the Byzantine period, or early fourth century,” Gibson says. “When the Byzantine inhabitants built there, they leveled things off a bit, but they used the same plan of the older houses, building their walls on top of the older walls.”

Sixth-century Byzantine emperor Justinian contributed another layer of preservation when he completed the construction of Nea Ekklesia up the hillside from the site. Construction involved excavation of enormous underground reservoirs, and workers dumped excavation fill downhill, burying the more recent Byzantine construction.

“The area got submerged,” Gibson says. “The early Byzantine reconstruction of these two-story, early Roman houses then got buried under rubble and soil fills. Then they established new buildings above it. That’s why we found an unusually well-preserved set of stratigraphic levels.”

The situation is more complex even than that because the area is a hillside. Some first-century structures appear to be at a higher level than some structures that are clearly Byzantine and built centuries later.

“In many places, reverse stratigraphy is going on,” Gibson says. “There is a hodgepodge of levels.” The site presents a puzzle of historical levels, reflecting not only a complex history but complex topography and changes to the landscape.

Buried in it all is a cultural story that must be sifted out and carefully analyzed, yard by yard. Doing this means hot, dusty work. Volunteer staffers carefully excavate everything by hand, examining each shovelful for artifacts. They put rocks and soil in buckets to be carried out of the holes by hand to “ballots,” fabric bags that hold about a ton of material apiece.

“We measure our diggers by how many ballots they remove,” Tabor says. “It’s usually about 30 a day.”

Digging Centimeter by Centimeter

If anything significant is found, the digging slows and the ground is excavated centimeter by centimeter. Every 10 centimeters or so, digging stops as workers take pictures and samples for analysis and run metal detectors across the spot to locate small artifacts that might be hiding in the soil.

In a section excavated this summer by a team under the supervision of UNC Charlotte Levine Scholar alum Kevin Caldwell, the work was particularly slow and careful. The first layers of Caldwell’s area were mainly fill, but soon the soil transitioned to discrete, undisturbed layers, which might have been missed if digging had not been extremely careful. A few more centimeters down, the diggers large amounts of uncovered fish bones, clamshells and fish hooks.

The significant find may support theories other archaeologists have made about the area. A bit after Saladin liberated the city from the Crusaders in the 12th century, there may have been a gate in this section of the city wall, archaeologists think, and perhaps a fish market outside the gate — hence the bones, hooks and clamshells, all of which would have come with imported fish. The site has also yielded large stones that may be remnants of this fabled gate.

In layers below the fish items, the excavators have found evidence of Crusaders — diverse artifacts, a glass earring, distinctive medieval horseshoe nails from northern France and other odd bits of metal. They also found pig bones, a giveaway that inhabitants were not Muslim. Site field director Rafi Lewis identified several of the metal pieces as tongues of belt buckles.

“These are classic conflict artifacts,” Lewis says. “When people fight, they grapple with each other and pull on sword belts and the belt metal snaps off.” The tiny rusted pieces may be an archaeological record of a famous battle between the occupying Crusaders and the army of Saladin.

Going down by centimeters, the site is packed with physical evidence of Jerusalem’s robust history.

“We have found material on this site from every historical period from the Herodian Roman through the Byzantine, from the Umayyads through the Crusaders, from the Ayyubids through the Ottomans,” Gibson says. Although there are no plans to dig deeper, the team has even found older material from the late Iron Age.

Gibson and Tabor predict at least two more seasons of digging at Mount Zion. With significant discoveries in the area in addition to their own, they hope the location will some day be turned into an archaeological park, a place where the site’s unique features offer people a “walk through history.”

Words: James Hathaway | Images: Rachel Ward

This story first appeared in the UNC Charlotte magazine.