English language learners in Mariella Duarte’s eighth-grade class at Whitewater Middle School in Charlotte face the steep task of learning middle school math in a language they have yet to master.

For these students, the cognitive load can prove overwhelming.

Anthony Fernandes, a mathematics professor at UNC Charlotte, is seeking solutions to that struggle. “There is a bias that teaching math to English language learners should be fairly easy,” he says. “It’s numbers and shapes. But how are you going to explain these numbers and shapes?”

Fernandes prepares future math educators and has turned his research focus to the unique challenges that English language learners face in math class. He has tapped into Cognitive Load Theory for possible answers to the dilemma. He works directly with students and educators in public schools, as well as his UNC Charlotte students.

“Our working memory has a limited capacity, but it plays a key role in problem-solving,” he says. “The job of working memory is to work with new pieces of information and draw upon the larger long-term memory, as well.”

Fernandes uses the game of chess to explain this theory. A fundamental difference between a novice and a Grandmaster is the cognitive load required to make a strong, strategic move. For the novice, each turn presents a brand new set of problems, obstacles, and potential solutions—and each is treated by the mind as a separate chunk of information.

On the other hand, the Grandmaster knows patterns. The brain of the Grandmaster treats whole situations as single chunks of information, well-known and easy to recall. Thus the cognitive load for the Grandmaster is significantly less taxing, providing a substantial upper hand in solving the problem: What’s my best move?

In the case of students learning math while still learning English, one solution is when students offload information from their working memories through good record keeping, which Fernandes says is as simple as “what students might scribble or draw.”

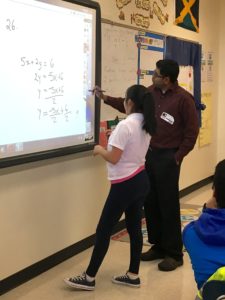

Anthony Fernandes works with a student.

With the support of a $300,000 grant from the National Science Foundation, Fernandes and his research partners hope to redesign mathematics tasks to encourage record keeping and make other changes. “We have to figure out what internal resources these students bring with them and how we can set up problems in a way these kids can make sense of them,” Fernandes says.

While analyzing interviews he conducted with English learner students from various schools, Fernandes noticed that students’ gestures did not always match the words they used to describe a mathematical concept. Perhaps most fascinating, the gestures were more reliable indicators of what the students knew.

For example, Fernandes noticed that a student had correctly defined area as “the inside of a shape,” but the student made a gesture of outlining the shape, rather than filling it in. Turns out, the student’s calculations had confused area for perimeter.

Fernandes, a mathematics educator, has found himself becoming well-versed in language acquisition, cognition, and multimodality. He has gained comfort in the world of a linguist, adding to the tools he can use to address the mathematical issues the students face.

“Increasing the scope of the communication modes gives these students more to play around with and more opportunities to be successful,” he says.

Duarte, an English as a Second Language teacher who holds two master’s degrees, sees the collaboration with Fernandes as critical to engaging her students. “Before, they weren’t participating, but now they want to do it,” she says. “They want to raise their hands, and they want to be the ones who go to the board and work the problems out. He opened their minds to like math.”

Within the first two months of working with him, students’ math scores went up – way up, she says.

Different methods and an increase in student engagement are certainly linked to the increase in student performance, but there may be another factor – hope.

“The students feel like they are learning, and they see that what we’re doing is really helping them,” Duarte says. “They see, ‘Hey, she’s a Latina, and he’s from India, and they’ve achieved things that we can achieve, too.’ They believe in themselves.”

North Carolina’s student population has seen an increase of about 400% in English language learners just in the past ten to fifteen years, and “the increase isn’t stopping,” Fernandes says. “We have to do something different.”

What is best for these English language learners may prove best for math education more generally. “What we’re doing is figuring out better ways to teach math, which ultimately benefits everyone,” Fernandes says.

Words: Brittany Stone | Images: Lynn Roberson and courtesy of Anthony Fernandes