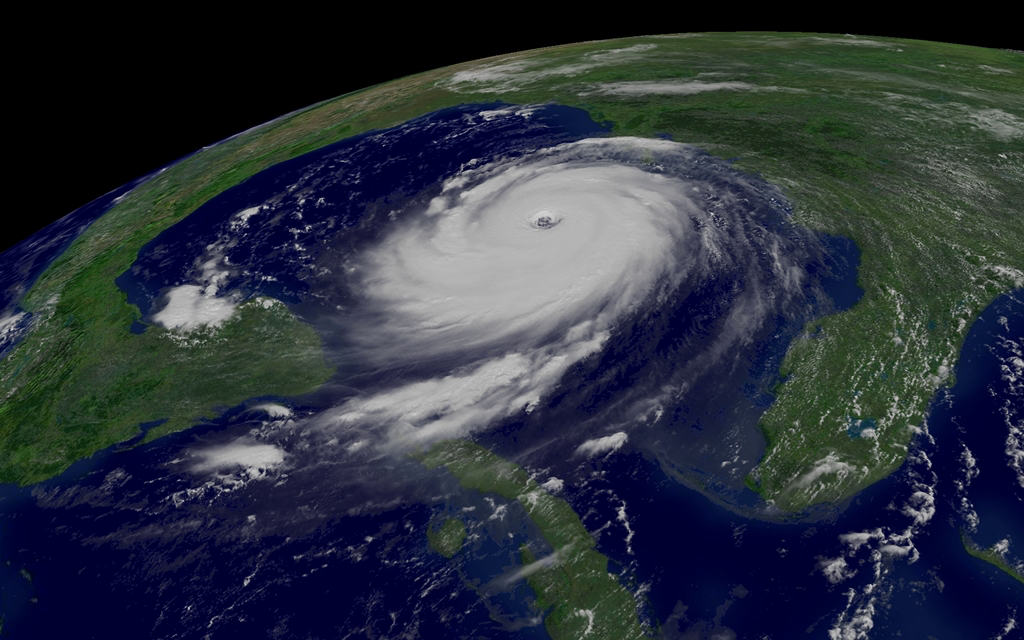

As Hurricane Katrina ravaged New Orleans in 2005, people worldwide converged around TVs to witness the devastation of an iconic city and government’s response to the storm. This catastrophic, life-altering event served as a pivotal point in UNC Charlotte researcher Cherie Maestas’ career.

“I was at a political science conference with my colleague and co-author Lonna Atkeson after Katrina hit,” Maestas says. “We, and everyone there, were glued to the TV in shock, watching the striking news coverage, trying to comprehend the human toll and anguish that was so apparent. Being social scientists, we wondered, if the news was affecting all of us this way, how was this news affecting broader public?”

Asking this question led to a National Science Foundation grant to conduct a nationwide public opinion survey, and Maestas’ new interest in the political psychology of public opinions.

When she came to UNC Charlotte in 2014 as the Marshall A. Rauch Distinguished Professor of Political Science, Maestas founded an experimental lab called POLS-LAB to study the effect of exposure to different kinds of emotion-laden media. She also has opened her lab to other researchers and students, to collaborate on studies each semester and encourage inquiry that crosses disciplines.

“The first part of my career focused on political elite behavior, with a goal of understanding what makes public officials responsive to citizens, and how the mechanisms of electoral risk and re-election drive that responsiveness,” Maestas says. “I’m now interested, more broadly, in understanding how people respond to information that triggers emotions of anxiety, threat and anger stemming from information sources in the environment, such as the news media.”

of electoral risk and re-election drive that responsiveness,” Maestas says. “I’m now interested, more broadly, in understanding how people respond to information that triggers emotions of anxiety, threat and anger stemming from information sources in the environment, such as the news media.”

With a heightened awareness of the extraordinary, catastrophic and shocking moments that touch people’s lives and influence their opinions, she and Atkeson, a professor at University of New Mexico, consider how people assess and understand the risks and uncertainties associated with democracy. Her research occurs at the nexus of communication and political psychology.

Based on their nationwide survey funded by the National Science Foundation, Maestas and Atkeson published a book on the topic, Catastrophic Politics: How Extraordinary Events Redefine Perceptions of Government (Cambridge University Press).

They suggest that such events are politically influential because they engage the public differently than routine political conflicts. This results in a public opinion environment that differs from the day-to-day, which enables political changes that would be less likely during more normal times, they say.

“Catastrophes bring together the public in a moment of high-anxiety and shock, and tell them something about the way the government is functioning in those initial moments right after the crisis,” Maestas says. “Strong emotions felt during catastrophes – even emotions experienced only vicariously through media coverage – can be powerful motivators of public opinion and public activism, particularly when emotional reactions coincide with attribution of blame to governmental agencies or officials.”

These catastrophes at the initial point show resistance to elite “spin,” or reframing as attempts to convince viewers to reappraise the information they are witnessing, so they are unvarnished views of how government responds, the research suggests. The events also engage more people than normally consume news reports.

“There are a lot of people out there who would never tune in to the news ordinarily, but if something blows up, or gets wiped off the map, everyone tunes in,” Maestas says. “These factors make catastrophes extra special moments in the way we understand how government works, and whether it’s working for all citizens in an equal way.”

POLS-LAB consists of a biometric station with galvanic skin response sensors, and 22 Internet-accessible computer stations. In addition to each having screen capture software and headphones, ten of the stations are equipped with video cameras for recording the subjects’ face muscles. These cameras take 30 different measurements per second, allowing a real-time analysis and calculations of emotions such as anger, joy and fear.

“We can really see which parts of the message are creating emotions in subjects, and then we can examine how that’s related to their political attitudes,” Maestas says. “This helps us understand how news events create conditions for punctuated policy change. People traditionally thought of emotion as being the opposite of cognition, and that people were either emotional or rational. But we’ve recently learned that emotion actually helps us be more efficient processors of information in many ways.”

Maestas is exploring how the public responds to information about drone strikes and shadow warfare, working with political scientist James Walsh. They seek to discover how mistakes or negative outcomes reported by news outlets about drone programs shape citizens’ subsequent support for related policies, and how the citizens apportion blame.

“The lab that Dr. Maestas is developing is a really ambitious effort to study political psychology in a sophisticated way,” Walsh says. “In particular, she is working on ways of unobtrusively measuring people’s emotional states, such as when they watch political information in news stories. The issue of drone strikes tends to elicit strong emotions, so that is an important area of overlap between us.”

Although POLS-LAB is part of the Department of Political Science and Public Administration, she encourages collaboration. She wants the lab to be seen as a resource and opportunity for all social sciences.

“One of the exciting things about POLS-LAB is that it really does open up opportunities for interdisciplinary cooperation” she says. My goal is to really foster this, and to encourage students and faculty, not just from Political Science and Public Administration, but from all across the college to become more involved.”

Words: Tyler Harris | Hurricane Image: National Oceanic and Administration/Department of Commerce